Humans & overpopulation are not the problem- The Gastropocene series Chapter IV

Local, multigenerational food systems & community as hopeful solutions

The Gastropocene series, co-created by

of and of , is a long-form discussion focused on the intersection of food, identity, ecology, politics, climate change and everything in between. How does the way we eat reflect who we are? What sort of actions can we take to build a sustainable food future? How has our separation from nature & community shaped our food practices so far and what can we do to reconnect? Previous chapters in the series:Chap I: What makes food ethical? — BEYOND Beyond Meat

Chap II: Climate or Ecology? — Re-contextualizing the climate emergency

Chap III: There is no one-size-fits-all solution to climate change — Abolish monocultures

As the COVID-19 pandemic progressed, there was a resurgence of ideas that yet again suggested that human beings as a species are to blame for environmental crises.

“Humans are the virus! COVID-19 is the cure.” “When humans are absent, the Earth is healing!” “Humans are the problem and to be blamed for climate change.”

Many framed the death and destruction unleashed by COVID-19 as much-needed cleansing and divine purging that was justified punishment for our collective sins. Many humorously hoped for more disasters of astronomic proportions like asteroid collisions that would systematically wipe out the human population, suggesting that our total extinction or at least a dramatic reduction in the human population was the “solution” to the planet’s ongoing pain that would finally allow for other non-human life to thrive. Genocide is essentially being proposed as necessary divine justice.

Fascism looks like- either 1) the blatant denial of escalating, catastrophic environmental/ ecological crises plaguing our planet (commonly called “climate denial”) OR 2) blaming humans (all or any select group of people) and overpopulation for being the root cause driving these problems (aka ecofascism). The latter is pervasive in environmental movements in the Global North. The overpopulation argument came about as a merging of BOTH these colonial ideas.

Origins of the overpopulation myth

In 1798, Thomas Malthus (now considered the father of overpopulation fearmongering) wrote an essay confronting what seemed to be the natural limits of societal expansion, stating that “the superior power of population cannot be checked, without producing misery or vice”. He argued that when food is abundant, human populations will grow at rates that will inevitably lead to food scarcity and famine. He believed that the solution was natural or government-mediated methods of population control including wars, diseases and poverty that would keep certain populations in check and maintain a “balance”. These words spoke to a greater fear that has erupted numerous times throughout history since then, from the explosion of Back to the Landers in the late 19th century to those which followed the same path 70 years later in the 1960s under the tutelage of Scott Nearing.

Malthus’ work inspired Paul Ehrlich’s apocalyptic novel “Population Bomb” in 1968 which raised global alarms over “unchecked” population growth in poor countries. The novel was based off Ehrlich’s tourist escapades in the impoverished slums of Delhi, India. He wrote “The streets seemed alive with people. People eating, people washing, people sleeping. People visiting, arguing, and screaming. People thrust their hands through the taxi window, begging. People defecating and urinating. People clinging to buses. People herding animals. People, people, people, people. . . . [S]ince that night, I’ve known the feel of overpopulation.” Ironically, at the time Delhi’s population was ~2.8 million while Paris’ was over 8 million. The former is a Brown city in the Global South while the latter, the capital of a colonial empire, was considered the emblem of human advancement and sophistication.

Famed environmentalists hoisted on pedestals in the Global North like Jane Goodall have stated that human population growth is behind our environmental problems and that said problems would be solved if our numbers shrunk dramatically to what they were centuries ago. Instead of blaming the poverty, inequity and environmental destruction unleashed by colonialism/ capitalism onto the world (which would require accountability), colonial thinkers have strategically blamed the victims of these oppressive systems. The narrative still plays out in so-called developed countries and ex-colonies where poor folks are judged for having children they “can’t afford” and blamed for taking up space. A lot of this logic was used to justify colonial conquests that aimed to wipe out, exploit and civilize barbaric, degenerate, backward peoples that were a demographic threat to so-called superior races.

Fears of overpopulation have threatened civilization since its inception; and for good reason. A bad harvest once meant hard times and death. How true are these words today?

Whitewashing of human history

Homo sapiens have been around for ~300,000 years. The vast majority of man-made widespread ecological destruction that has significantly damaged the planet and all it’s inhabitants emerged in the last couple of hundred years. This is the era of massive, ever-expanding and conquering colonial empires and nation-states. Capitalist society and exploitative systems are not a linear, universal human endeavor 300,000 years in the making. These are relatively new, destructive inventions that dramatically altered the trajectory of planetary life systems.

Some humans profit off of the destruction of the planet while others dedicate their existence to preserving the land and fostering relationships that care for our ecosystems. In “The Solutions Are Already Here”,

aptly summarizes this point:“Saying that humans are responsible for ecological devastation is a continuation of colonial racism, and it is an insult to the peoples who have fought against obliteration to preserve their way of life and their relationship with their territory. It is also an insult to the many people who, despite growing up in a culture totally infused with the values of capitalism, have risked their lives and freedom to defend the land and halt destructive development projects. And it is an insult to the hundreds of millions who are subjected to extreme poverty or absolute precarity by the very same economic order that profits from ecocide, who have to worry about their personal survival and that of their family and community, and do not have the luxury of choosing between different job opportunities and consumer products based on how “ecological” they may be…

People in the Global South— people dehumanized by Western slavery, colonialism, and racism— finally get included in the category “human”, just in time to share the blame for the devastation caused by a social system that has ravaged them far more than they have profited from it.”

What many people consider to be “human history” is often skewed to favor colonial narratives and selectively omits histories that would threaten the existence of current systems. The widespread lack of awareness of how human societies operated in ways that nurtured the land rather than destroyed it, is in itself a byproduct of colonial erasure.

Too many people? Or too many large-scale, exploitative systems?

Today, the world population hovers around 8 billion people, more than double of the population just a century before, and on track to reach 10 billion people by 2050. From a conventional agricultural perspective, most scientists believe our current food consumption practices could support 10 to 12 billion people, which would, in theory, mean we are looking at reaching maximum capacity within this century.

There’s a few issues with this perspective; the first is that the way we frame food production.

Many scientists argue that we can support that population if we turn all arable land into agricultural lands and go vegetarian. Of course, we’ve addressed why this is patently false, and that it once again reinforces a dichotomy of us against nature, when in fact much of the non-arable land produces plenty, especially under the guidance of Traditional Ecological Knowledge.

Further, our conventional food system shows us that we are more than capable of growing food at scale today; we currently produce enough food to feed 10 billion people, and a third of it goes to waste.

This is a reminder that calls to increase production are misguided, we need to be better at getting food to the people who need it and entirely re-think the way capitalism has mass produced food so far. The best way to get food to people who need it is to localize food systems so food isn’t lost in transit and so that food is democratically owned by communities, assuring equity and access. Under agroecology, our food systems are by definition local; they are framed within local ecological conditions, meet local ecological needs, shaped by local cultural traditions and are driven by indigenous plants for healthy, resilient ecosystems. These ecological systems are complex systems; what this means is that their increasing diversity also increases resiliency and efficiency, meaning the same space can support more living things, including people, while giving us the best chance against the coming climate change crisis.

Our understanding of food production is often shaped solely by our experiences with capitalist systems where profit-driven food production is synonymous with ecosystem destruction.

If we look at the world thru the lens of existing structures, without ever questioning these structures themselves, we will inevitably cause more damage trying to “solve problems”. We cannot accurately assess the maximum carrying capacity of our planet based on TODAY’S models of growing food because we currently have a very poor measure of what our ecological systems could actually carry. We’ve written extensively about the dangers of movements that claim that ethical “environmentally conscious” food production involves a global adoption of vegan, plant-based diets and an abandonment of diverse ancestral, local, traditional systems which are painted as “unethical”, uncivilized, savage and destructive to the planet. This and the “overpopulation” advocates approach food thru a consumerist lens where people are still reliant on monocrop plantation based, state-controlled, corporation-produced food rather than locally-grown, community-driven food systems that honor local ecology and culture.

We have seen historically systems like the Mayan Milpa which have carried population densities similar to modern densities utilizing local foods and local resources and areas which would be considered “non-arable land” today that fed millions in the past. To limit our thinking and to imagine that we cannot, with the resources available today, adapt these historical practices that were refined over hundreds, if not thousands of generations for specific ecosystems to feed the people who exist on the Earth today is to ignore the great ingenuity of the human species.

Today’s extractivist food production systems separate humans from nature but when we’re entangled in a web of ecological relationships, the amount and quality of food we’d produce will be drastically different.

Community-based food systems, in their progression towards increased efficiency, self-regulate more effectively thru systematic iterative processes. What this means is that when humans become embedded within their ecosystems, population self-regulates. While we don’t have proof of this in humans, we do have evidence that high-population changes reproduction interests and works as a self regulatory system species-wide. The fact that today population rates are slowing and many scientists believe that when human population hits 11 billion we will likely plateau speaks to the fact we are very unlikely to actually reach any conventional metric of “overpopulation”.

While the overpopulation argument is valid on its surface, it is hollow in substance and reflects on a colonial, limited, mechanistic view of our planet shaped by inefficient, exploitative systems that were designed to fabricate scarcity not feed everyone. While there are limits in what the Earth can support under the current system, the argument is flawed because it is predicated on conditions which will never materialize. Still, there is no quantitative scientific assessment that can accurately determine the maximum life-giving capacity of our planet given the complex variables that go into shaping said capacity. The concerns of overpopulation are unwarranted, and the issues are instead regarding access and equity, and the need to re-localize ourselves within a bigger ecological context.

Placelessness- A brief history of modern food systems

So how did we get here? How long have we been eating off of grocery shelves? Entire books have been written on the subject, but much of our conventional food system is rather new. That doesn’t mean that shelf stable foods are new. Storable starches have been a part of nearly every society, both hunter-gatherer and civilized, of our entire history. Exotic foods traveled across continents tens of thousands of years ago; the idea of eating foreign foods and exotic spices is not the byproduct of colonization, but rather the byproduct of humanity sharing and exploring and celebrating the surpluses of their ecological communities.

When we talk about our modern food system, however, we have to be extremely careful; the idea of storable foods isn’t inherently a bad thing and that the idea of hyper-preserved foods is not necessarily a consequence of whatever flavor of ‘ism’ you happen to be against. When we criticize the current food system, we can parse out necessary and unnecessary food storage techniques. For example; when we discuss the need for foods to store for years– is that because we need foods to be available years from now, or is it a byproduct of a food supply chain whose food is so disconnected from any community’s needs that the cost of overproduction and hyper-preservation is offset by the volume of food which would otherwise be thrown away, which is also compared to the costs of producing at a smaller (and less profitable) scale. This financial matrix drives our food system, and as we’ve talked about in the past, is colored by a world driven by artificially cheap fuel and transit costs.

The processing itself is not a problem. When that processing is decoupled from a community, its needs, and its health, it quickly escalates into a world where diabetes, heart disease, chronic illnesses and many other issues have become growing health concerns. The idea of placeless foods has accelerated only in the past two centuries and coincided with the industrial revolution, a petroleum-based economy, and grew exponentially with the advent of petrochemical fertilizers and increased access to global markets thru railways. Global migration created further demand for foods that reflected cultural histories, and fetishization helped create new markets for these same cultural relics even further.

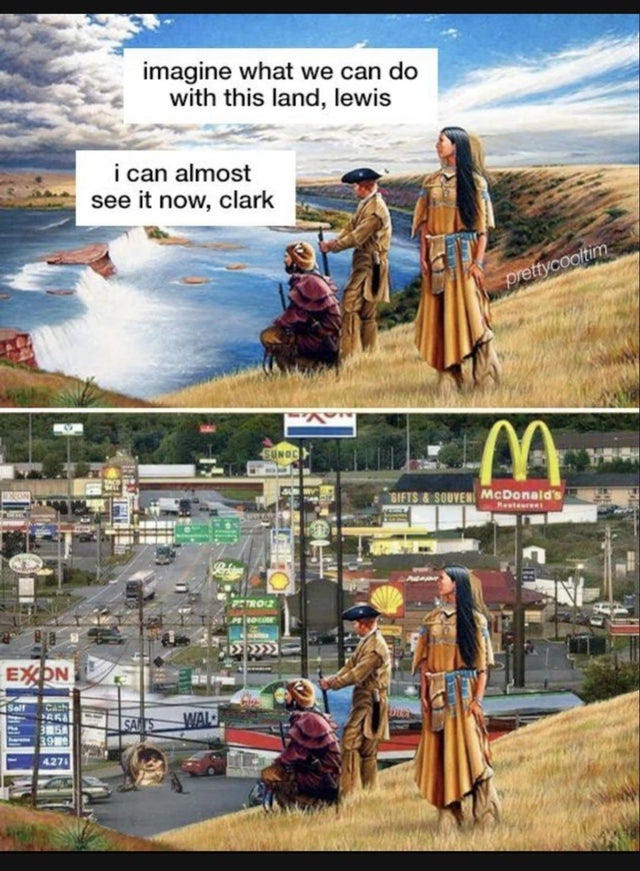

In short, our food system, which once was a reflection of place and community, is an entangled mess in the name of security, profits, and a yearning for place, whether due to migration or simply living in a commodified world that is by definition without place. When your culture is the rotting highways of suburban McDonalds, gas station hot dogs, food desserts and fast food chains, anything else is an appealing alternative.

So what do we do? — Understand local ecology

How do we address this placelessness? And further, how do we address placelessness when our homes exist on the literal graveyards of genocide and whose former stewards are today advocating for their unceded lands to be returned? Conversations about land back & rematriation are complex and nuanced, and can only be addressed at a communal scale. But as individuals, we can take first steps in learning our local native flora, fauna, and its history. Our role is to restore the landscape for that resiliency, that complexity as we had discussed before, and in that process take some of the first steps towards a better future.

We can grow food, and we can grow food understanding that a community garden will not feed a community. It’s not just about feeding a community, it’s about rebuilding a relationship with the natural world around us that we are a part of. It’s about rebuilding fractured communities which have become isolated nuclear families due to the loss of what sociologist Ray Oldenburg called ‘third places’. Third places exist as community strongholds for people to connect with one another, and historically have acted as places that provide classless overlap. As income inequality continues to rise and polarization has further pushed people to believe the worst in others, finding spaces to connect as individuals is more and more important. And as these third places become more out of reach for poor & middle class people, with disposable income at an all-time low, finding places where we can connect, build reciprocal relationships, and find ways to restore some sense of community and collective identity will be of significant importance.

Multigenerational systems— growing food for the future

The most resilient food systems do not just focus on how we will feed ourselves within our lifetime. We need to grow food for the future. Realists will argue that growing chestnuts, hickories, black walnuts, and even oaks for food is naïve- people will not eat them, there is no infrastructure for these crops, that their taste profile doesn’t mean the modern palate. This is the precise logic of capitalism that has driven ecological collapse- individualistic, profit-driven models of economic growth are short-sighted by design. They are operated by power-hungry, self-absorbed people who ignorantly try to thrive at the expense of others in the present and future generations while also neglecting the many lessons of the past that clearly tell us what does & doesn’t work. The walnuts, the hickories, and the keystone oaks? We plant these nut trees for future generations to develop food systems around.

The most sustainable food systems require us to do two things: 1) understand our ancestral traditions and collectivist histories that will inevitably pass down critical knowledge about our ecosystems and food practices that have effectively sustained our communities while preserving the land we rely on, and 2) build food systems that aim to feed our future generations.

Learning from the past

Those of us that are born into a society shaped by capitalist values are often cut-off from the intergenerational passing down of knowledge, ideas, experience and expertise- particular when it comes to food systems. Some of us may have some intergenerational cultural and religious/ spiritual practices including diverse gastronomic traditions. The problem is we are often limited to understanding our ancestor’s food practices thru consumption of products on grocery aisles rather than growing our own food like they once did. On a planet ravaged by colonial displacement, many of us do not have access to the local ecology within which our traditional communal recipes were created.

However, it is important now more than ever for us to dig deep into the stories and techniques behind these recipes- why were specific ingredients were used, when and how were staple foods grown or harvested, what steps were taken to nurture soil fertility & nourish the land, how was food processed and prepared communally, etc. We must understand our gastronomic traditions in the larger context of the relationships our communities had with their local ecology. Then we can begin to apply these lessons to our current context, wherever we are. From diverse heirloom seeds to diverse heirloom food preparation rituals- stories and knowledge passed down across multiple generations will help us survive.

Like relearning to build the pyramids, today we are only just beginning to relearn the skills and systems that our ancestors had perfected over hundreds of generations. That isn’t to say our goal is to go back, but rather to learn how we can marry the resources & technologies of today to perennial crop systems which enhance our ecosystems, further give life to the natural world around us, and give our children and grandchildren the tremendous task of building from what will likely be a very faulty foundation.

Grow for tomorrow

When we think about the type of food we want to grow- a shift towards thinking long-term, even beyond our lifetimes pushes us to diversify our practices beyond focusing on plants with annual high yields. What type of seeds do we need to plant today that will yield sustenance 50 or 100 years down the road if not longer? What types of plants do we need to bring into our ecosystems that improve the longitudinal fertility of our soils gradually such that even if they don’t provide us with abundance today, there will be abundance for our children? The overall integrity of an ecosystem increases when there is a vast diversity in the types of life and the cycles of time that they synchronize with. Some plants yield annually or biannually, perennials yield every few years, and others yield in time intervals that we don’t fully understand yet. How can trees that lay dormant for years and suddenly produce an abundance at random in response to incomprehensible environmental cues be helpful for us to plant?

An example: Nut Trees and Masting

Nut trees don’t yield every year. They produce at unpredictable intervals in which many barren years are suddenly succeeded by a boom and bust of an overabundance of nuts- a phenomenon called mast fruiting. They have provided both humans and other animals across history with nutrient-rich sustenance when it is most needed (like during food scarce winters). Nut trees are more resilient to drastic climate shifts, stabilize ecosystems to prevent habitat destruction, improve soil integrity and serve as niche wildlife habitats themselves. These trees put in years of labor and love to gather the critical proteins, oils and carbohydrates they need to pack into each nourishing nut.

In the book “Braiding Sweetgrass”, Robin Wall Kimmerer describes how pecan trees synchronize their fruiting cycles so all trees produce nuts as a collective:

“If one tree fruits, they all fruit— there are no soloists. Not one tree in a grove, but the whole grove; not one grove in the forest, but every grove; all across the country and all across the state. The trees act not as individuals, but somehow as a collective. Exactly how they do this, we don’t know yet… The pecan groves give, and give again. Such communal generosity might seem incompatible with the process of evolution, which invokes the imperative of individual survival. But we make a grave error if we try to separate individual well-being from the health of the whole. The gift of abundance from pecans is also a gift to themselves. By satiating squirrels and people, the trees are ensuring their own survival . The genes that translate to mast fruiting flow on evolutionary currents into the next generations, while those that lack the ability to participate will be eaten and reach an evolutionary dead end. Just so, people who know how to read the land for nuts and carry them home to safety will survive the February blizzards and pass on that behavior to their progeny, not by genetic transmission but by culture practice.”

Industrial capitalist food production systems focus on maximizing yield for high profit margins. Feeding future generations requires us to take a fundamentally different approach- one where we focus on building reciprocal relationships, don’t take more than we need to feed the community (i.e. local inhabitants) and ensure that we are giving back to the land ten times more than we intend to harvest from it. Feeding our children requires us to think about not just what the land can do for us today but ask how we can care, nourish and nurture the land to feed other flora/ fauna and protect it from harm. We need to, just like the masting pecans, pass down crucial knowledge and cultural practices to the generations that will come after us.

Intergenerational knowledge is not something that is solely passed down thru our biological family lines. It is knowledge that we obtain by sharing time and space with people in any kind of communal context. If we’re building foundations of what will be a total upheaval of food production systems as we know it- we need strong, intimate relationships that will also serve as multigenerational and cross-community knowledge streams.

“The pecan trees and their kin show a capacity for concerted action, for unity of purpose that transcends the individual trees. They ensure somehow that all stand together and thus survive. How they do so is still elusive… In the old times, our elders say, the trees talked to each other. They’d stand in their council and craft a plan. But scientists decided long ago that plants [were] locked in isolation without communication… Science pretends to be purely rational, completely neutral, a system of knowledge-making in which observation is independent of the observer. And yet the conclusion was drawn that plants cannot communicate because they lack the mechanisms that animals use to speak.”

Western science takes a mechanized approach to nature and in its obsession with reductive quantification, it fails to account for the complex, subjective, amorphous factors like the key role that love and community care play in increasing the nutritional value, sustainability and efficiency of our food systems. The most sustainable and nutrient-rich food will come to us when we grow it as part of a web of reciprocity- i.e. nurture our relationships, pour our love and care into the land honoring that it is our universal caregiver, take what is given with gratitude, use it for sustenance and not for power or wealth hoarding, and reciprocate the gift by planting for future generations.

That is our task. To provide the resources for future generations to build from. And to do that, we need to build alongside members of our community today. Inadvertently, the practices that come from us thinking about feeding the future will improve the resilience of our relationships & food practices today. It will take time, patience, practice & adaptation and that is our task.

With Care,

Andy & Ayesha.

“Exploitative systems... designed to fabricate scarcity, not feed everyone.” 🌟 Yes

Thank you Ayesha ❤️ This affirms my desire to relate with the ecosystem/ my community in a nurturing way ❤️